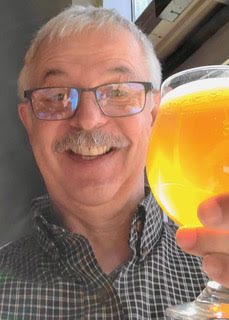

Life as an RCMP can be heroic to those on the outside. But for Patrick Guy Roy, his life works as an RCMP has not only left him with stories but has brought on PTSD. In a memoir that Patrick is writing, he talks about life as an officer, his PTSD, the struggles of being an officer, and some heroic stories to boot.

Who can you say has impacted your time as an officer the most, whether it was a partner/co-worker or a criminal/suspect you were trying to take down?

Who can you say has impacted your time as an officer the most, whether it was a partner/co-worker or a criminal/suspect you were trying to take down?

There were two pivotal moments in my career that I wrote about in my book, Fighting the Good Fight: The Memoir of Patrick Guy Roy, and they stand as polar opposites on the emotional spectrum. One was terrifying, and the other was highly fulfilling and life-affirming.

I was involved with a young man, Darren Roode. The first time I was called to his residence (he lived with his parents), he was barricaded in his bedroom with a shotgun pointed at his chin. He was delusional and thought that the devil possessed his girlfriend. I was able to disarm him without incident, and he was taken to the psychiatric hospital. A few months later, the detachment received a call from Roode’s doctor saying that Roode was heading home, weapons were in the house, and the doctor was concerned. I was just about to get off shift, and I had plans with my wife that evening to attend a Christmas party when a co-worker asked if I would assist since I had been to the house before, and I was familiar with the suspect. I immediately said yes. I should mention it was the only day in my entire career that I had opted out of wearing my bulletproof vest. I felt a little under the weather that morning and was running a mild fever, so I decided to leave it at home. It is difficult still to write about this situation without the anxiety churning in my stomach.

This time Darren Roode was aiming the gun at us. I was there with my partner, and two other officers had shown up to assist. We were all in the house, myself and Cst. Caughey down the hallway from Darren’s room wedged in beside the door jam of his parents’ room. Cst. Morrison was in the living room. Suddenly Darren shot through the wall of his room and hit Cst. Morrison. Cst. Caughey and I heard the piercing bang and wailing screams but were entirely in the dark as to what happened. Fortunately, Morrison was only hit in the hand and managed to crawl out, but that left Caughey and me still in the hallway. It was a no-exit situation. We had to run into the line of fire to make our way to the side door. Thankfully, Darren decided not to shoot, as I would have been dead for sure. Ultimately, I ended up in a shoot-out with Mr. Roode. He was injured and taken to hospital, and there were no other fatalities or injuries at the time. I say at the time because, after this situation, I was a changed man – this was when the PTSD set in for me. I write extensively about this whole situation in my book, and the process did help me to gain some emotional distance.

The second situation revolves around an international child kidnapping. Mark Habib Eghbal had slashed his wife’s face resulting in forty-six stitches, and he illegally fled France with their three-year-old daughter Sara. He had been at large for three years. Word came in over police bulletins that Mr. Eghbal and Sara had been in Toronto and were possibly travelling east. At this time, I was on special detail working on a drug interdiction pipeline. My partner was on holiday, and another officer asked if he could ride along with me and learn the ropes. I readily agreed.

On special detail, we were trained to spot out-of-province cars and look for particular signs indicating that they were carrying drugs. I soon spotted a vehicle with Ontario plates (we were in Nova Scotia), and I pulled up behind to give my colleague a briefing. This was when I noticed a young girl running across the backseat without a seatbelt. This gave me the lawful right to pull the vehicle over, but when I pulled up beside the driver and saw him slouching down, I knew I had something. My chest constricted, and my heart was pounding. It was my innate spidey-sense telling me there was more to this than a seatbelt infraction.

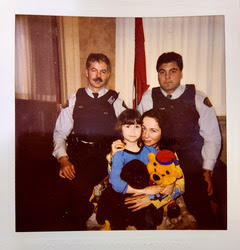

To make a long story short, it was Sara, the missing girl. I was able to secure her safety. Her mother, Fabienne, was notified in Toronto, and she immediately flew to Halifax. I brought Sara to the Halifax airport for the reunion with her mother. It received quite a bit of press at the time, and it reinforced why I was an RCMP officer. It was a moment of pure joy to bring a little girl back to her mother. Fabienne and I have stayed in touch visiting each other’s families in France and Nova Scotia, and we exchange pictures and texts frequently. I recently had a video call with her father just before he passed away, as he specifically asked to speak with me before he died. They are all very special people to me.

Finally, working as an RCMP officer is like being part of a family. The majority of my co-workers were exceptional human beings who risked their lives daily to save others. There are also auxiliary RCMP officers who volunteer to help our communities. They don’t get paid for their service, and without them, we would have been screwed. The administrative support I received from the brilliant women in the various detachments kept the machine going. We couldn’t do our jobs without them. It truly is a kind of family when you are working in a position where you are dealing with the most nefarious side of our society.

What can you say is the most controversial part about being a member of the RCMP?

What can you say is the most controversial part about being a member of the RCMP?

One of the most controversial parts of being a member of the RCMP is the misconception that proliferates in the press regarding police officers in general. There is no perfect system, and there are bad cops, and every good cop wants the bad cops gone. However, there is so much you go through daily that the general public has no notion of, and I’m not suggesting they should, but it is never talked about in the press. For example, after the Darren Roode shooting, there was no debriefing. I had a couple of beers with the other officers, went home to my wife, tried to sleep and reported for work the next day at 8:00 am. In a 10 hour shift, you could be apprehending a drug dealer, visiting a violent domestic situation, reporting on suicide, and pulling over a car for speeding. I think people forget we are human and that we emotionally react to the various cases. If I have to tell someone their loved one has been in an accident or is dead, I grieve with them. Not just when I tell them, I also grieve when I go home and when I wake up in the night. I can’t just wash that away. Still, to do our jobs, we must continually compartmentalize our emotions and get on with it. It’s an intense internal rollercoaster of emotions that never ends.

In what way do you hope your story can be heard, especially when sharing the emotional aspect of PTSD in the workplace?

I hope that more male and female officers who have suffered seek help and speak up about their traumas. During my tenure with the RCMP, there wasn’t a lot of support for our emotional well-being. It was a suck-it-up environment, and I believe things have changed, but I still think work needs to be done. I’ve learned the hard way that suppressing my emotions or negating them altogether only harms me and those I love. I think the more we talk about PTSD and workplace trauma, the better off everyone will be. I also think we need a more balanced view of policing. I understand the media’s need to expose corruption, but I think the imbalance of reporting contributes to a warped view of officers. We are people with wives, husbands, kids, parents, siblings, and friends. We hurt as much, if not more than most, as we are so aware of the horrors that are going on in our societies. I worked as a child sexual assault investigator for two years. Those were exceptionally hard years. Being a cop is a job that leaves your heart filled with a lot of irreconcilable sorrow.

Telling your life work to the world is very vulnerable. What made you want to share your story?

I was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s in January of 2020, just shy of my sixtieth birthday. A year later, I decided I wanted to tell my story. First, as a legacy to leave my children. I have three beautiful children, Alyssa, Aidan and Abbie. I thought it would be a great memento for them and maybe something they might want to share with their children one day. Second, I wrote my memoir to try and help rid myself of my PTSD and as an exercise in memory retention. Then as time went on, I realized that my story might help other RCMP officers or their family members understand them better and the trauma officers endure. Finally, I thought it might help other men who have been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. We fellas tend not to want to be vulnerable or talk about our feelings. I’ve reached a point where I have nothing to lose, so if I can still help others, that is what I want to do.

Article published by HOLR Magazine